LIFESTYLE

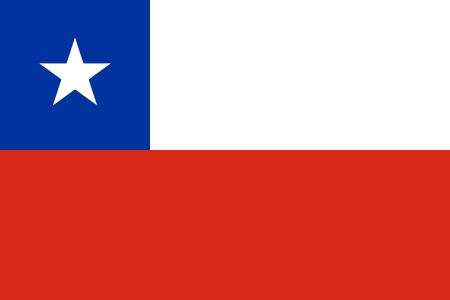

Le drapeau du Chili : couleurs, signification

Le drapeau du Chili, surnommé “la estrella solitaria” (l’étoile solitaire), a été officiellement adopté le 18 octobre 1817. Il est composé de deux bandes horizontales …

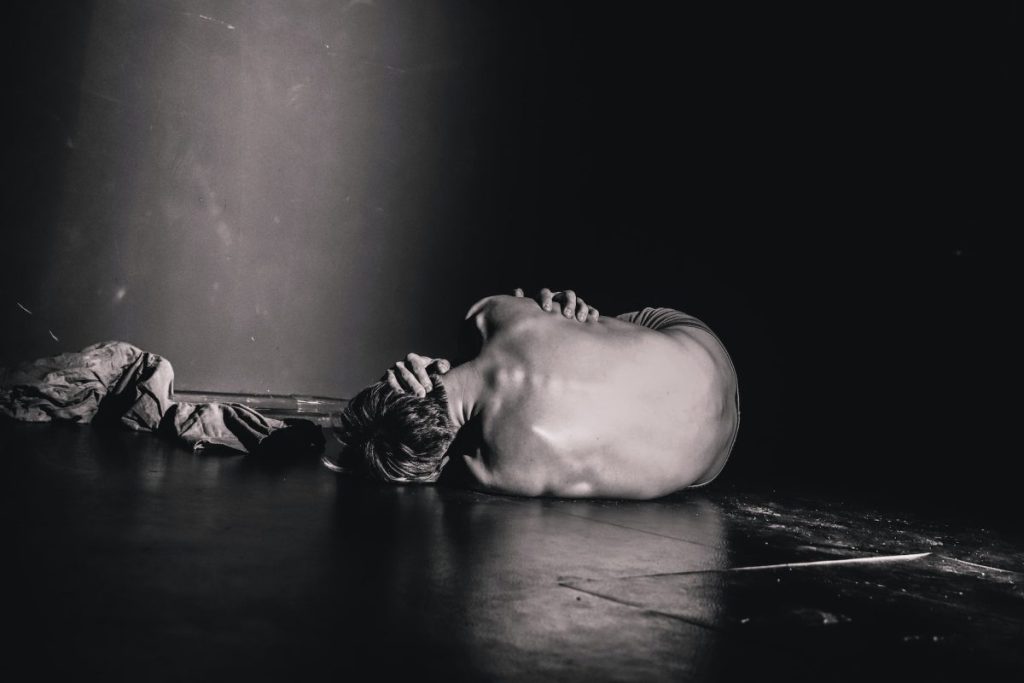

Read moreQuelles sont les 5 phases de la dépression ?

La dépression est un trouble psychologique qui touche de nombreuses personnes dans le monde. Elle se caractérise par des sentiments persistants de tristesse, d’inutilité ou …

Read moreDrapeau de Cuba

Conception du drapeau: Se compose de cinq bandes alternées et d’un triangle équilatéral rouge avec une étoile blanche au niveau du palan. Officiellement adopté le …

Read moreSanté

Société

Les noms de famille allemands : D’où ils viennent et ce qu’ils signifient

Si vous avez fait des recherches sur vos ancêtres allemands, vous avez probablement passé beaucoup de temps avec leurs noms de famille. Vous vous êtes …